Consumer-Driven Contracts for SQL Data Products

dbt announced "model contracts" in the recent v1.5 release. This looks like a great feature for dbt, but reminded me that I've been using contract testing with dbt for a couple of years now, inspired by Pact consumer-driven contracts, but never talked about it. There are some differences, for example: dbt's new feature is very dbt-centric, the approach I've used isn't - dbt certainly helps, but it isn't necessary. There's a GitHub repo to follow along with.

Why Contract Testing?¶

Pact's Introduction gives a great overview of what contract testing is and why you need it. Borrowing their words to explain what a contract is:

In general, a contract is between a consumer (for example, a client that wants to receive some data) and a provider (for example, an API on a server that provides the data the client needs).

For an API-based digital product interface, a consumer-driven contract might say that in response to a query API call, the consumer expects a response in JSON containing a property "userId" that is a string. The provider can test any changes against the contract to ensure they do not break this expectation. The contract provides a means and a motivation for the consumer to clearly express important expectations.

The same approach works with the same benefits for a SQL-based digital product interface. In this case, the same contract might say that in response to a SQL query, the consumer expects a tablular result containing a column "userId" that is a string.

The Digital Jaffle Shop¶

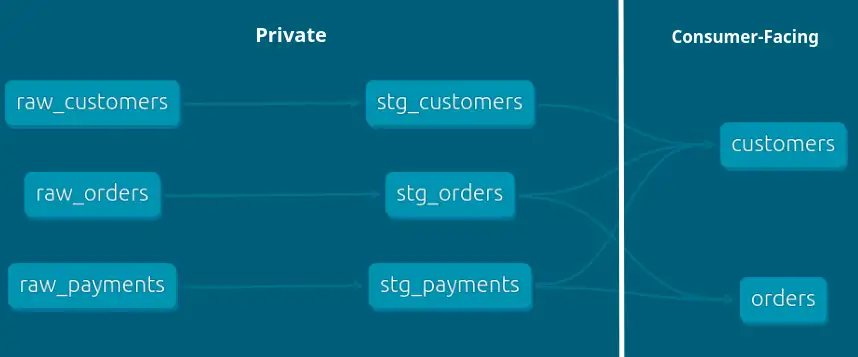

I'll show you what I mean with dbt-labs' Jaffle Shop demo project as our producer, and we are the product team looking after it. In the lineage graph below, we can see some raw relations1 feeding some staging relations to produce a customers and an orders relation.

The right-most relations, customers and orders, are our customer-facing interface. The "upstream" relations are implementation details and hidden from consumers, ideally by permissions. Besides potentially protecting more sensitive data, this hiding of implementation detail from consumers is important for stable contracts. Without it, we lack the flexibility to adapt to change whilst holding the contract stable.

Consumers can only see orders and customers, so we only accept contracts against these relations.

Jaffle Sales¶

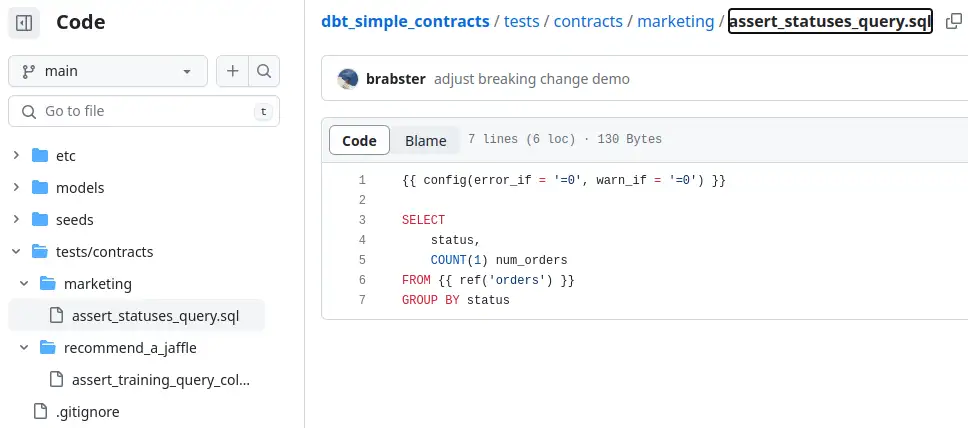

Marketing need to run a variety of ad-hoc reports about orders in the various order statuses. They don't want to come in one morning to find their queries don't work, so they want to make a contract. With our help they put together the PR for this SQL.

{{ config(error_if = '<3', warn_if = '<3') }} -- configure the test to fail if there are not enough statusres

SELECT

status,

COUNT(1) num_orders

FROM {{ ref('orders') }}

WHERE status in ('complete', 'returned', 'return_pending')

GROUP BY status

What expectations are expressed here?

- this specific, important (to the consumer) query works

- there's a status column

- there's a row in the results for each of the specified statuses (by the error_if config)

- the SQL dialect I'm using works with the provider's warehouse

Well, it's maybe not how I would have written it but I understand it and it works. Let's move on.

Recommend-A-Jaffle¶

The CEO is convinced that the next big thing in the jaffle industry is recommendations, so we've got a new consumer. This consumer needs to know a little about customers and orders, then they'll join that with other information in the business and perform some machine learning magic.

After some heavy duty, caffeine-fuelled data sciencing, the recommender team settles on this query to produce the data they need to train and test their model:

SELECT

customer_id,

order_id,

order_date,

status

FROM jaffle_shop.orders

WHERE order_date > CURRENT_DATE - INTERVAL 90 DAY

The data produced by this query is munched by some machine learning models wrapped in Python code. The team building the consumer product is working flat out and could really do with some reliability from the producer, so they're happy to pop a ticket on the board to set up a contract with the Jaffle Shop producer.

The recommender team could start simple with the query as it stands as a contract. We can turn it into a test that the expected columns are present and correctly typed like this:

SELECT

customer_id + 1, -- number

order_id + 1, -- number

order_date + INTERVAL 1 DAY, -- date-like

status || 'x' -- string

FROM {{ ref('orders') }}

Those operations on each column look a bit weird, but they effectively assert column type and generally produce a reasonably informative error message. I'm not making a statement on correctness of that approach, but if a consumer proposed it as a contract I'd have a hard time arguing the clarity and simplicity of it!

What both teams need is a way to provide their tests to the Jaffle Shop team in such a manner that it must pass before a change can be rolled out. I'll show you what I think is the simplest way to do that next.

A Simple Provider Contract Test Setup¶

We create a subdirectory of tests/contract in our dbt project. We'll have each consumer contribute their tests directly via a merge or pull request process. dbt will, by default, run their tests as part of a build or test operation.

Let's run a dbt test for everything under contracts and see what happens...

jaffle_shop$ dbt test -s contracts

...

21:29:39 1 of 2 START test assert_all_statuses ...................... [RUN]

21:29:39 1 of 2 PASS assert_all_statuses ............................ [PASS in 0.07s]

21:29:39 2 of 2 START test assert_training_query_columns ............ [RUN]

21:29:39 2 of 2 PASS assert_training_query_columns .................. [PASS in 0.04s]

21:29:39

21:29:39 Finished running 2 tests in 0 hours 0 minutes and 0.25 seconds (0.25s).

21:29:39

21:29:39 Completed successfully

21:29:39

21:29:39 Done. PASS=2 WARN=0 ERROR=0 SKIP=0 TOTAL=2

So far so good - if the consumers had submitted a contract test that didn't work against the current product then our pull request process would have caught it and prevented any confusion.

Roles and Responsibilities¶

When a consumer team submit their PR, we have an opportunity to take a look and request changes before accepting. The recommender team's contract, for example, could be expensive as it actually processes every row in the relation, even though it's really just doing a schema test. Depending on our database technology, we could ask them to use the information schema to do that, or just add a LIMIT 0 so that the query optimiser can recognise that no processing in necessary and optimise it away.

A key consideration in my approach to this is that the provider is not forced to accept a consumer contract. Providers are naturally incentivised to try to accept consumer contracts. Besides the stability and insights benefits, a consumer-driven contract capability shifts some responsiblity for stability from the producer onto consumers. A consumer can't really blame a provider for breaking something they never said they needed.

The provider must be able to refuse unreasonable or incorrect expecations, so that the emphasis is on a collaborative effort between equal parties for mutual benefit.

Move Fast and (Don't) Break Stuff¶

The Jaffle Shop data sources are seed .csv files. The column types are inferred from the data. That means that in the Jaffle Shop data, IDs are integers. The product team notices this unexpected behaviour and decides to fix it (in principle IDs are strings, not integers and on the data warehouse technology they use, strings are more efficient as join keys). They start that change, adding a snippet of YAML to dbt_package.yml, telling dbt to treat order_id (which is column id in seed raw_orders) as a string.

They refresh the seeds and run a full build...

jaffle_shop$ dbt seed --full-refresh && dbt build --exclude contracts

05:45:48 Running with dbt=1.5.0

05:45:48 Found 5 models, 22 tests, 0 snapshots, 0 analyses, 313 macros, 0 operations, 3 seed files, 0 sources, 0 exposures, 0 metrics, 0 groups

...snip...

05:45:55 28 of 28 START test unique_orders_order_id ................. [RUN]

05:45:55 28 of 28 PASS unique_orders_order_id ....................... [PASS in 0.04s]

05:45:55

05:45:55 Finished running 3 seeds, 3 view models, 20 tests, 2 table models in 0 hours 0 minutes and 2.74 seconds (2.74s).

05:45:55

05:45:55 Completed successfully

05:45:55

05:45:55 Done. PASS=28 WARN=0 ERROR=0 SKIP=0 TOTAL=28

Voila, nothing broke2. This is a Safe Change ™. Let's check the contracts.

jaffle_shop$ dbt test -s contracts

06:13:16 Running with dbt=1.5.0

06:13:16 Found 5 models, 22 tests, 0 snapshots, 0 analyses, 313 macros, 0 operations, 3 seed files, 0 sources, 0 exposures, 0 metrics, 0 groups

06:13:16

06:13:17 Concurrency: 1 threads (target='dev')

06:13:17

06:13:17 1 of 2 START test assert_statuses_query .................... [RUN]

06:13:17 1 of 2 PASS assert_statuses_query .......................... [PASS in 0.07s]

06:13:17 2 of 2 START test assert_training_query_columns ............ [RUN]

06:13:17 2 of 2 ERROR assert_training_query_columns ................. [ERROR in 0.04s]

06:13:17

06:13:17 Finished running 2 tests in 0 hours 0 minutes and 0.26 seconds (0.26s).

06:13:17

06:13:17 Completed with 1 error and 0 warnings:

06:13:17

06:13:17 Runtime Error in test assert_training_query_columns (tests/contracts/recommend_a_jaffle/assert_training_query_columns.sql)

06:13:17 Binder Error: No function matches the given name and argument types '+(VARCHAR, INTEGER)'. You might need to add explicit type casts.

06:13:17 Candidate functions:

06:13:17 +(TINYINT) -> TINYINT

06:13:17 +(TINYINT, TINYINT) -> TINYINT

Usage vs. Contracts¶

A lot of insight into expectations can be gleaned from reviewing usage logs - which queries were run, by whom, when. I've found some challenges in doing this well, in particular that without "platform" support, a provider on a modern data warehouse won't have the usage information as it will have been logged in the consumer's account or project which the producer won't have access to.

Even if it worked well, there's still a gap. A contract allows a consumer to express a critically important query that must work, but is only run, say, once a year as part of financial year end reporting. That's a big benefit. Those infrequent, important queries are easily missed and broken!

Comparison to dbt Model Contracts¶

I've not yet played with the new contracts functionality, let alone used it in anger. My goal here is to get my own thoughts and experience clear, so this is a quick comparison based on my reading of the documentation in May 2023 - it's shiny new functionality so the documentation may have changed by the time you read this.

dbt's current documentation doesn't say anything about consumer-driven contracts. Having consumers be able to express any need they have and having traceability back to who needs it is my basic goal in coming up with this approach. A contract that the provider creates for themselves isn't what I'm trying to achieve.

The current dbt contract approach prohibits arbitrary queries as tests and explicitly only supports schema-based constraints. This means that there must be a translation from what the consumer needs to what dbt contracts accept. It's also clear that there are expectations that consumers may not express, because they involve data quality. This reminds me of a surprise I had with dbt analyses back in the day - I expected to be able to use them as part of the test suite but in fact they are only compiled. Maybe you can set things up to use your existing analyses as contracts...

Does that matter? If I am a consumer of your "employee" data, and I expect the values in the "employee_id" column to be unique, or the values in "status" to be one of a set of values, I'd like a way of expressing that to you in a runnable form. When you look at my PR, you can correct my understanding if it's incorrect, and you can catch changes that would break that expectation. In the event that the issue is introduced in one of your sources and you are running regular automated data quality testing, you will catch that in your test run and be able to react more effectively knowing what the problem is and who is affected.

Downsides¶

This approach will be making some assumptions about the environment, for example use of git-based processes, automated testing and environment setups. Perhaps a future post will describe the setup I advocate for and why.

The cost of running the contracts will likely be attributed by default to the provider team, not the consumer team. That doesn't seem like a big deal, in my experience the internal dbt test suite is way more involved and expensive than the contracts, and there's value in the provider understanding the consumer needs that likely outweighs the cost for an organisation.

Contracts may effectively duplicate the same tests. This is a feature, not a bug. If two consumers have a common expectation, you still need to link the expectation to both providers. I've not found it to be a problem. You also can't use the declarative tests that dbt provides via YAML schemas, as far as I can tell - there can be only one definition of tests on a column.

Summary¶

I think that consumer-driven contracts are important to run Data as a Product, one of the four Data Mesh Principles (no apologies for being a fan!). A neat thing about the approach I've outlined is that the benefits come with no need for additional software, services, or "data plaform". I prefer a more "living off the land" approach, using tools I'm already using - in this case source control, a CI system, SQL and optionally dbt. Less to learn for me, less to learn for everyone I'm working with.

In the approach outlined here, your consumers have full access to the power of SQL to make their assertions, and whilst dbt streamlines things, it's not strictly necessary that either provider or consumer uses it - the approach hinges on SQL can be adapted to suit your tooling. I think the only really dbt-specific thing I've used is ref - and if you're not using dbt, you'll have your own solution to swap out references if you need to change them as part of your quality assurance.

I'm in two minds about using ref. Consumers can't directly use your refs. By using a ref you're creating the possibility of the provider changing the location of a relation and having all the contracts pass, when the consumers queries will fail. Ideally you want to run contracts before you deploy to consumers, but consumers will refer to the relations you actually deploy to them. Expect an update at some point when I have a nice solution for this!

A more flexible and powerful approach would have a separate repo for your contract tests. It's more to setup and manage, but gives access to the full capabilities and ease of use of dbt for contracts. Your consumers can define their queries as models and then make fine-grained assertions for them. You can deploy their models into a separate, suitably permissioned schema or database where they can be inspected for additional diagnostic capabilities.

edited 2023-06-14 for clarity and added commentary on use of

ref

-

I use the less common term

relationrather thanviewortablebecause arelationisn't specific and could be eitherI avoidmodelas it is a dbt-specific implementation detail rather than the interface consumers actually interact with. ↩ -

No, I didnt rig the tests. Made the change and the tests just all passed. Surprised me too, but it was quite useful for this post! ↩